I was watching these online videos from The Irish Times "After the Asylum" and they brought me back. Not to the asylum. I mean the people in the videos weren't in real asylums either; they closed years ago. They were in psychiatric hospitals or on the psychiatric wards of general hospitals. I was watching them thinking this is the reality. Mental illness isn't a pop singer having a fit of the jitters before going on stage or some teacher complaining because she's too many copies to correct. This is the thicker end of the mental health wedge.

What do I remember?

I must've never heard of David Rosenhan's "On Being Sane in Insane Places" study or else I wouldn't have tried it. I had just been chased through the ground-floor corridors of a large teaching hospital. I had been sent to the A&E there and I was trying to escape. Like that was ever going to work. I was cornered and was in a room with some staff, including a youngish doctor. She had long blonde hair, was wearing a blue blouse or shirt, and had big blue eyes. I remember thinking I could trust her. If you've never had a room full of people look at you in the certain knowledge that you're extremely mentally ill and possibly dangerous, you won't know how I felt.

She asked me was I hearing voices. This was a standard question and I usually answered truthfully. But my trust in this doctor, and my desperation, made me take a truly crazy leap. I knew that mad people heard voices and that they often had religious delusions and these could be mixed together. So I came up with my religious delusion/ hearing voices mash-up.

"Yes I do."

"What do they say?"

"They say I'm Mary Bernadette." I was thinking of Bernadette of Lourdes but getting a bit confused. Mary was also a name I associated with madness, I'm not sure why. I went on about visions and things for a while. Why did I do this? She was a young doctor, close in age to myself. I remember thinking that she'd go "Ah, go on out of that". That she'd turn around and tell everyone that I wasn't really mad, that I was faking it. You see, I was mad in a way, just not in the way they thought I was.

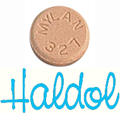

"They say I'm Mary Bernadette." I was thinking of Bernadette of Lourdes but getting a bit confused. Mary was also a name I associated with madness, I'm not sure why. I went on about visions and things for a while. Why did I do this? She was a young doctor, close in age to myself. I remember thinking that she'd go "Ah, go on out of that". That she'd turn around and tell everyone that I wasn't really mad, that I was faking it. You see, I was mad in a way, just not in the way they thought I was. I can still see the round, pale pink pill on the table. It was Haldol. There was no way I was taking that. No way I was. For about five minutes.

"If you take the pill we'll let you go."

Well, that was a no-brainer wasn't it? I took it and by the time they had me in the car for the transfer to the unit appropriate to my geographic area, ( that turned out to be their version of "letting me go") I was groggy and the whole world had taken on fuzzy, blurred edges. My mouth was dry. I could offer no worthwhile resistence. So I just offered what I could.

Why did I do that? Why would anyone lie to a psychiatrist and say they heard voices, and invent what those voices were saying? Why would anyone take a powerful major tranquillizer, knowing the unpleasant effects, and also that it was being prescribed totally inappropriately? Why would anyone do that if he or she wasn't insane? Isn't the status of psychiatric patient proof enough of serious mental health problems? I mean, they don't go locking people up for nothing, do they?

Why? is a question I ask myself now. Why did I ever go back there? Why did I keep going back over and over, and even now, sometimes fantasise about lying on a bed in a dimlylit room with no responsibility beyond breathing? It was a case of touching the devil and not being able to let go.

I thought they would help me. I thought they would fix me. I thought they would read my diaries and understand. That's how I got involved in the first place. I wanted to go on one of those ten or twelve week inpatient eating disorder programmes. I thought I'd come out all fixed. And part of me thought it would be great having a big, long break from being me. Me being what I now recognise as a false self, who spent every waking minute, and lots of dreaming ones, trying to figure out what people around her wanted and how they her wanted her to be.

In the end I never completed one of those programmes. I remember how it ended. It was around two years after the lying-about-hearing-voices episode and I had finally been referred, at my own request, to probably the most well-known inpatient eating disorders programme in the country. I'd recently spent four weeks in the same hospital, not doing any programme, mostly just hanging around being cured of my delusions. I was back for my pre-admission interview for the programme. I said I was vegetarian and asked could I be excused from eating a fry every morning. He said no, the fry was compulsory and in his experience no-one ever recovered from an eating disorder while remaining vegetarian. I suspect that he saw vegetarianism itself as a psychiatric symptom. I looked across the desk at this man, who was pre-eminent in his field, the country's leading expert on women and girls like me and I made the decision not to do his programme, though I didn't tell him there and then. I went home and thought about it, and decided it'd be me and my DBT workbook against the world. Did I make the right decision? I'll never know, but I don't regret it.

In the end I never completed one of those programmes. I remember how it ended. It was around two years after the lying-about-hearing-voices episode and I had finally been referred, at my own request, to probably the most well-known inpatient eating disorders programme in the country. I'd recently spent four weeks in the same hospital, not doing any programme, mostly just hanging around being cured of my delusions. I was back for my pre-admission interview for the programme. I said I was vegetarian and asked could I be excused from eating a fry every morning. He said no, the fry was compulsory and in his experience no-one ever recovered from an eating disorder while remaining vegetarian. I suspect that he saw vegetarianism itself as a psychiatric symptom. I looked across the desk at this man, who was pre-eminent in his field, the country's leading expert on women and girls like me and I made the decision not to do his programme, though I didn't tell him there and then. I went home and thought about it, and decided it'd be me and my DBT workbook against the world. Did I make the right decision? I'll never know, but I don't regret it. I've other memories too. There are too many to hold in my head all at the one time so they flit in and out, some staying longer than others. Most often they provoke anger at how I was treated but some of them evoke guilt and shame as I remember times when I was actually quite aware. At times I used a whole wing of the health service to for my own ends, to prove how upset I was or to demonstrate that I was being responsible and tackling "my issues". Was I mentally ill? I don't know; I think I might have been but not in the way they thought I was. One of the nurses told me that I was just like a diabetic and needed my medication the way a diabetic needs insulin. For years I felt outraged at that analogy and it is true that no insulin-dependent diabetic would survive without insulin for the nine years it's been since I took a psycho-active pill. But maybe it isn't too inapt an analogy; after all there are non-insulin dependent diabetics who can control their condition through diet and exercise and lifestyle. And there's a grey area where people can decide to take the pills or take the responsibility.

The whole time I spend as a patient no-one ever suggested to me that there was anything, anything I could do to improve my situation. My role was to accept my status as mentally ill, to gain insight into my condition, and most importantly, to comply. I look back now and think what were the words that would have made the most difference to me? Not "We're going to try something new. It's called Zyprexa. Has transformed the lives of millions of young people like you..." but "There's nothing wrong with you. You're fine. You don't feel great and everything is hard but you're fine. You're normal."

No comments:

Post a Comment